Geographical context

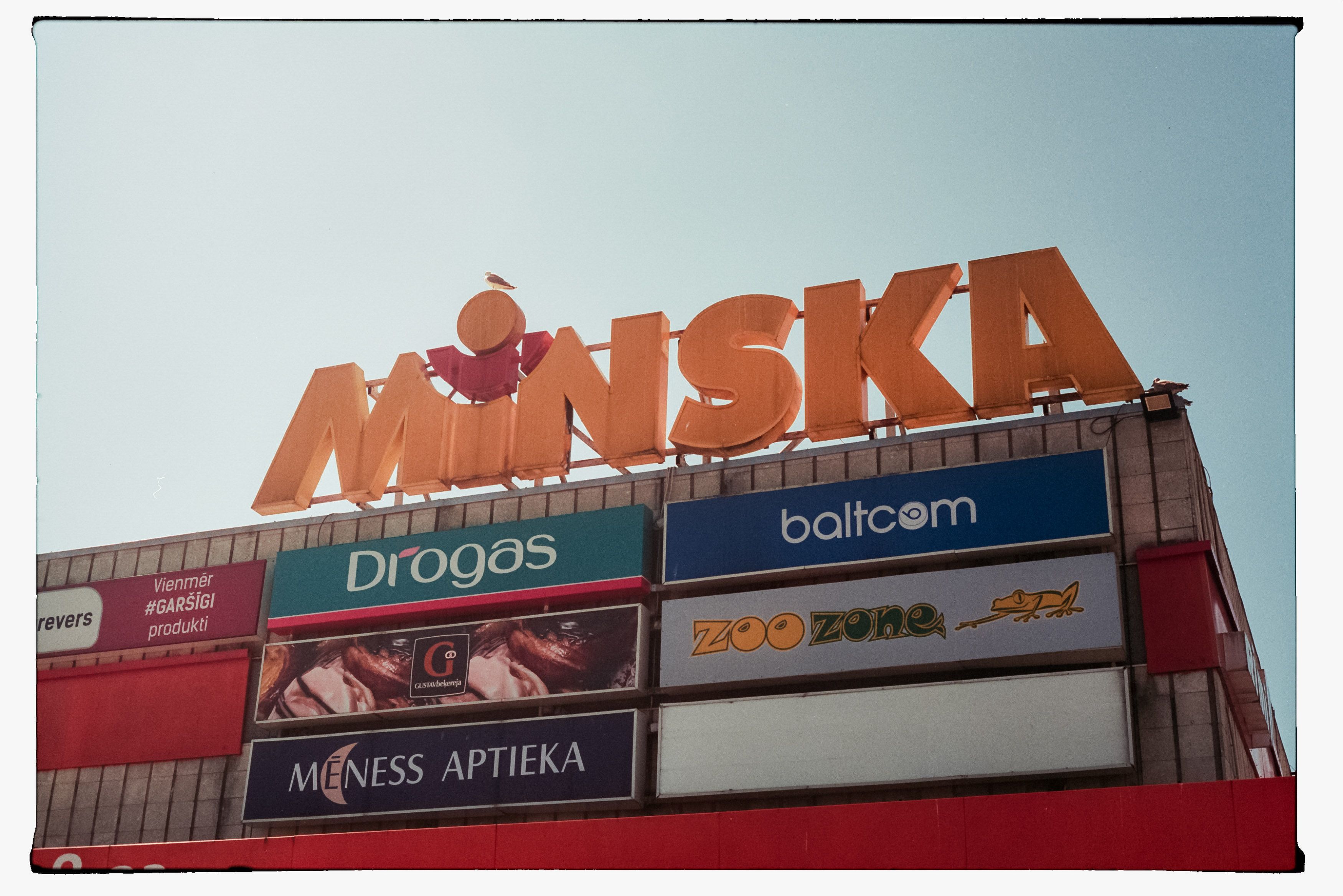

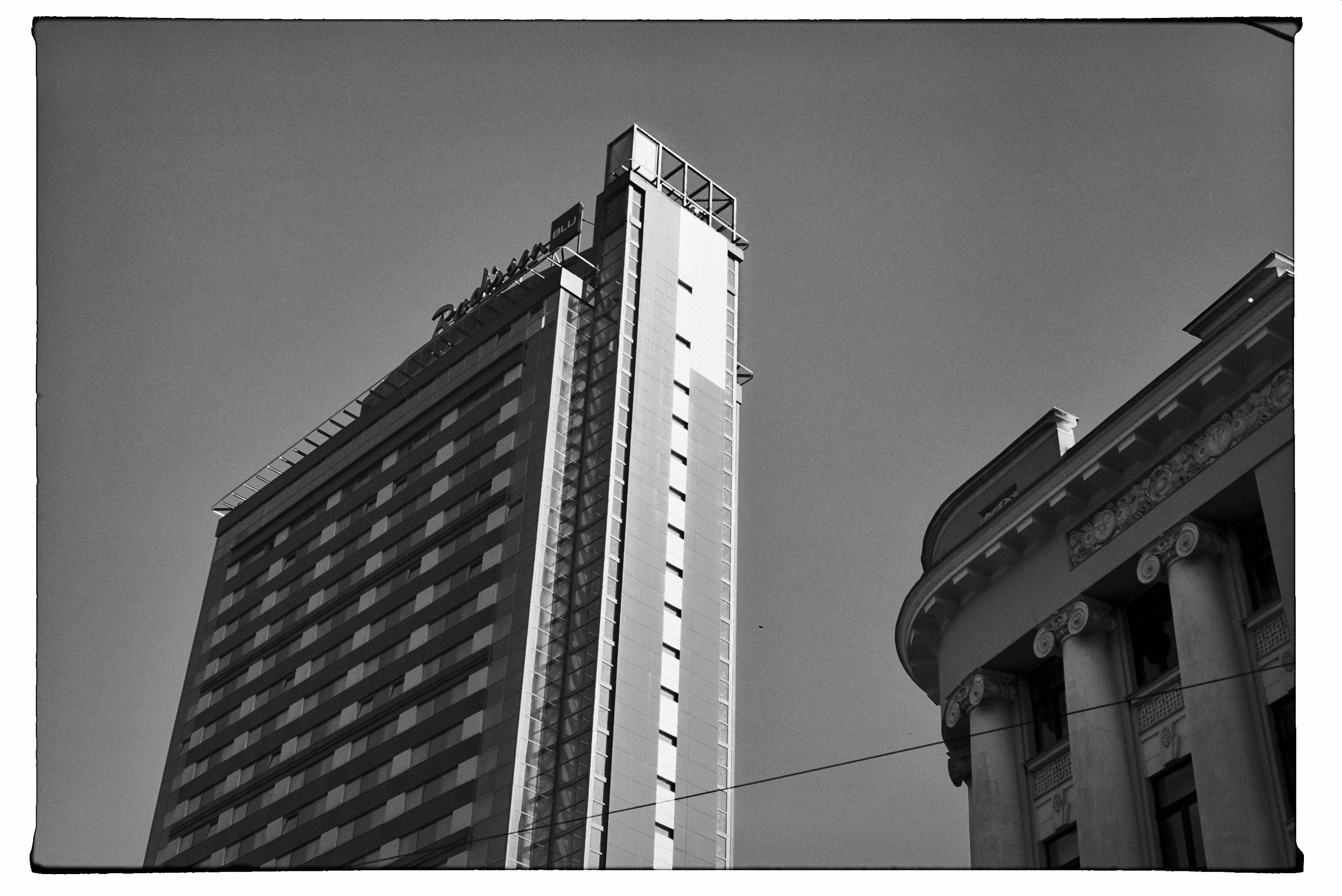

When asked which countries had been a part of the Soviet Union, many might point towards nations such as East Germany, Poland, or perhaps Bulgaria. While it is in fact true that these countries all had communist regimes, and heavily influenced by the politics of Moscow, they were de jure not a part of the Soviet Union. This is in contrast to the Baltic states. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were three Soviet Socialist Republics (SSRs) until the Union’s collapse. They were in essence “states” of the Soviet Union. Between 1991 and 2004, a period of merely 13 years, the Baltics would make history on three separate occasions: The first time – in 1991 – would come after the fall of the Soviet Union, when the USSR collapsed. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania regained their independence after a 51 year long Soviet occupation. The second time would come in 2003, when the three countries requested membership to the European Union, and it was granted. This marks the first time – and as of 2024 the only time – where formerly Soviet nations were granted entry into the European Union. The third time they created history was in 2004 when the countries became members of NATO. This is a political anomaly, as no other formerly Soviet states have been granted that privilege. These facts combined make the region both strategically and politically significant to Western powers; especially in the face of the current Russo-Ukrainian conflict. The Baltic states were NATO’s only border with Russia until Finland’s accession in 2023. A narrow 100km wide passage connects the Baltic members to its NATO neighbour of Poland to the South. This small stretch is flanked by the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad to the West, and the heavily Russian influenced state of Belarus to the East. With that context in mind, this book aims to provide insight into the Baltic states during the early summer of 2023, to experience and document the architecture, landscape and culture of some of the EU’s most politically significant member states of the 2020s.

Khrushchyovka

The Khrushchyovka was the Soviet Union’s first attempt at designing cheap and quick-to-construct housing, it was the answer to the intricate and eloquent “Stalinist” architectural style which Stalin had fostered in the Soviet Union. After the end of the Second World War, there was an acute housing shortage. With men returning from the front, and many structures destroyed, a swift solution was required. This solution came in the form of the Khrushchyovka. The design of this type of residential apartment block – named after the contemporary president of the Soviet Union Nikita Krushchev – had a major innovation at its core. The economics of the situation were quite simple, the Soviet Union needed to provide roofs over the heads of millions, and it set out to provide those roofs for next to no financial burden on its prospective inhabitants. This required a significant shift in the architectural paradigms of the early 20th century. The solution which Soviet architects had come up with had gained popularity during the wartime years. Instead of constructing the building in-situ brick by brick, concrete panels would be purposely cast in factories and transported to the construction site. This – in theory – saved a lot of time due to standardization and cut costs due to the repeated operation of producing the same panels. Most Khrushchyovkas would end up being five floors or fewer. This particular number of floors was chosen because of a legal requirement in the contemporary Soviet Union. Any building counting 6 or more floors required an elevator. In an attempt to avoid the costs that installing an elevator would entail, most Soviet architects simply chose to narrowly avoid the legal requirement.

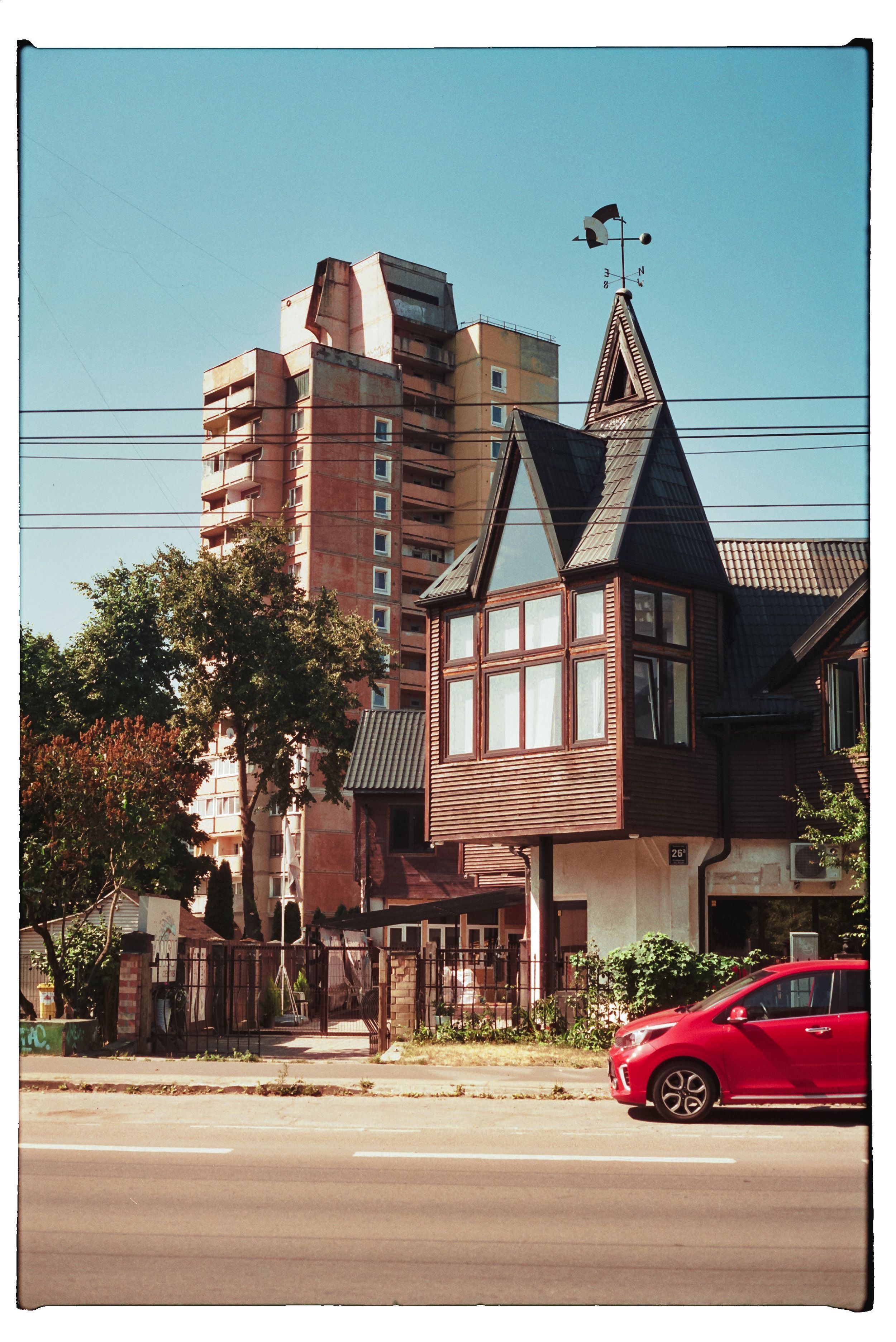

Claiming the balconies

One might notice from the get-go when looking at a Soviet-era high-rise is the cacophany of architectural styles displayed on its facade. While most apartments were state owned, making modifications to them was a legal grey area which many people made use of. With Soviet residences being especially small, cramped and poorly insulated, many of its inhabitants decided to build ameliorations to their uncomfortable dwellings. This often took the form of adding walls or windows to their balconies, which provided two major benefits: The first being the added insulation against the cold, the second being the extra indoor space that the expansion provided. The construction of the addition was left completely to whims of the inhabitant of the appartment. For a lot of buildings, this resulted in a rather ecclectic outward look.

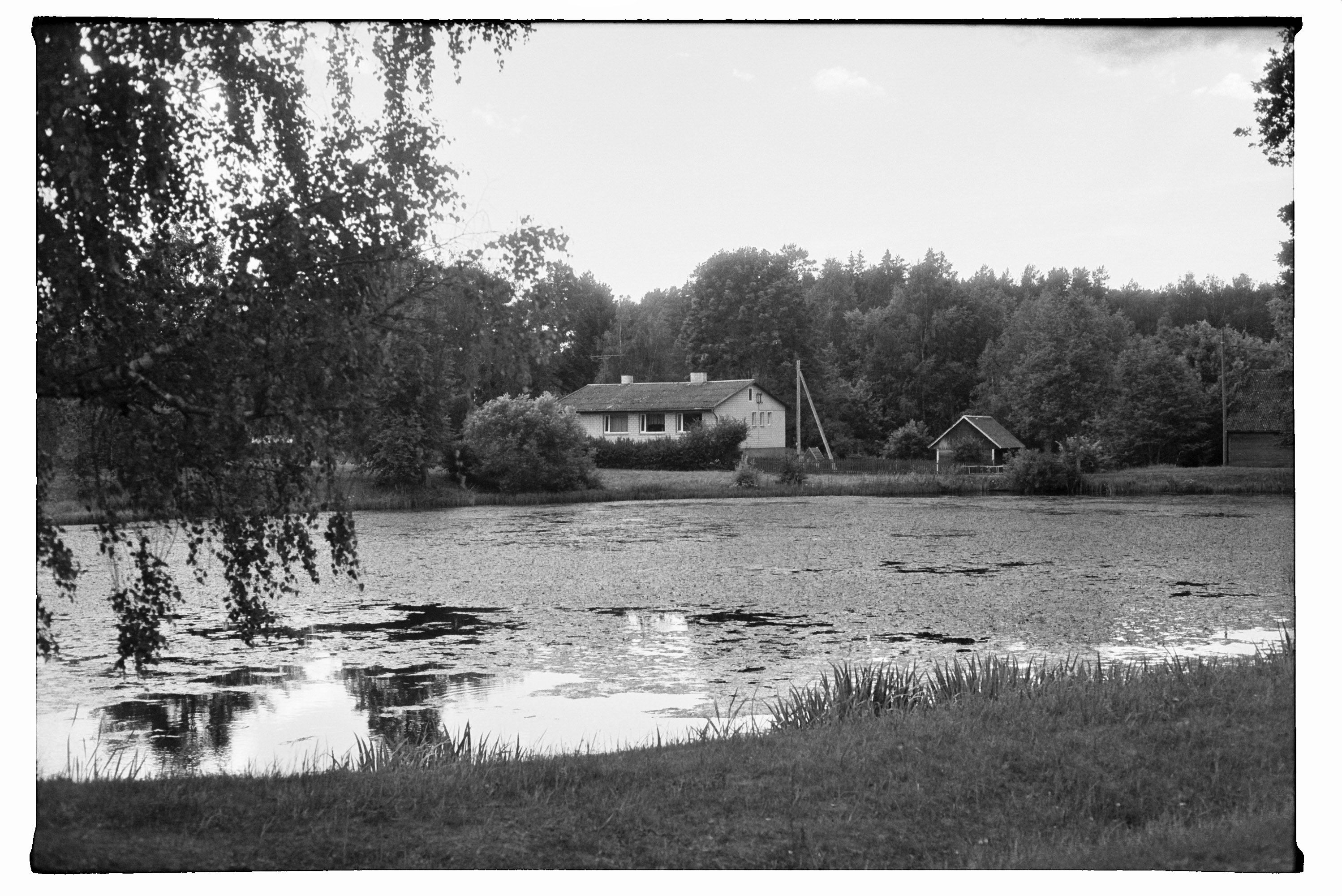

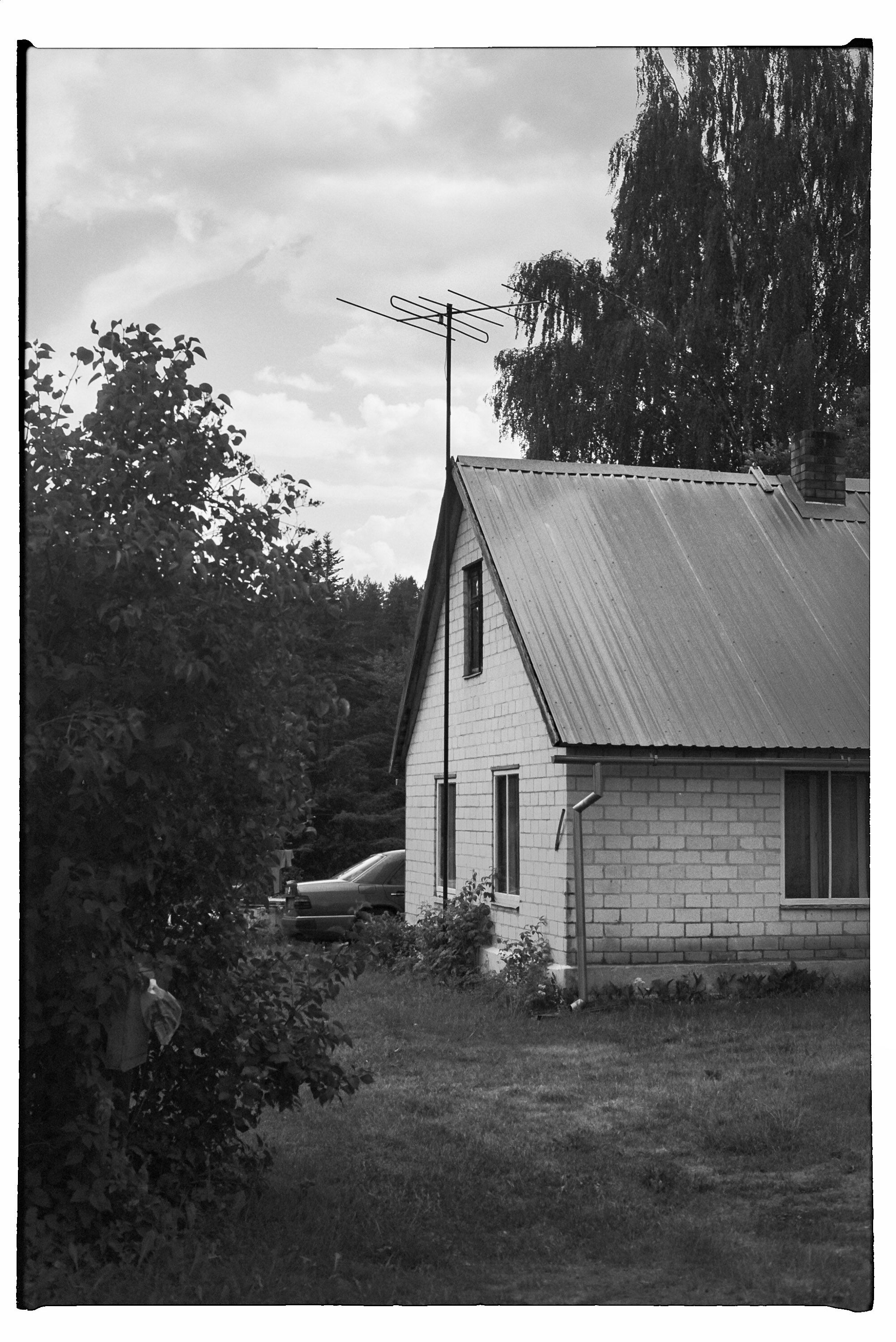

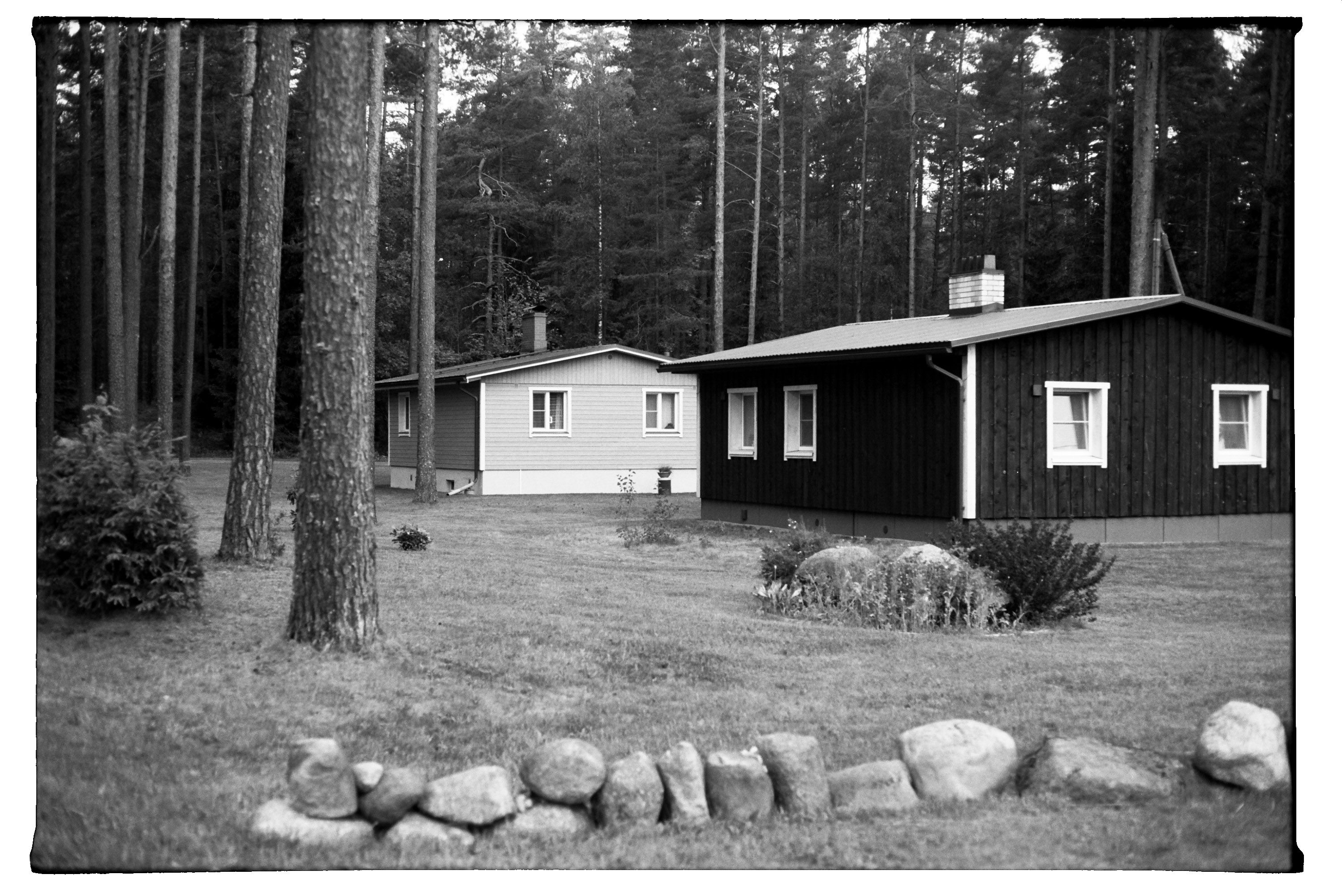

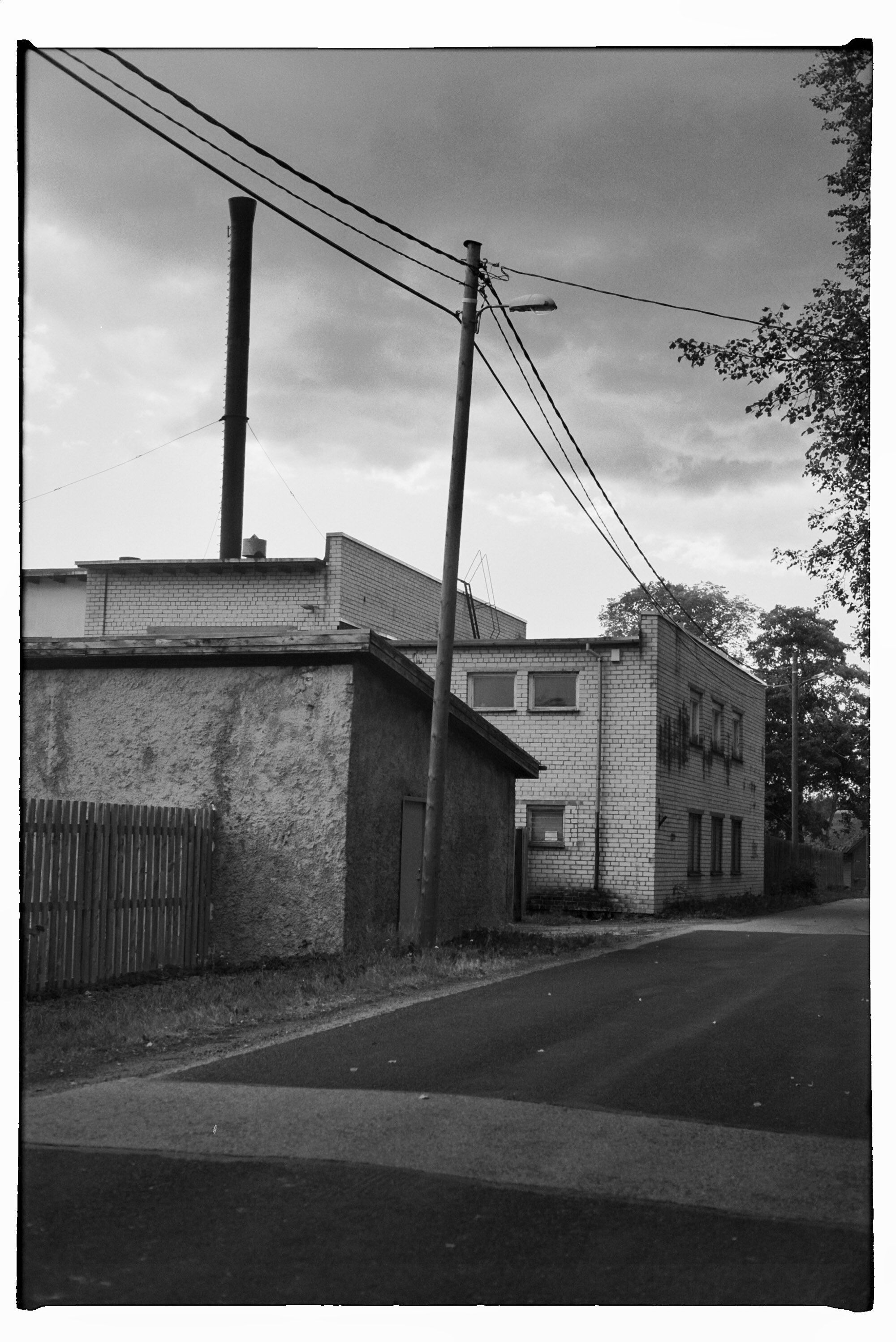

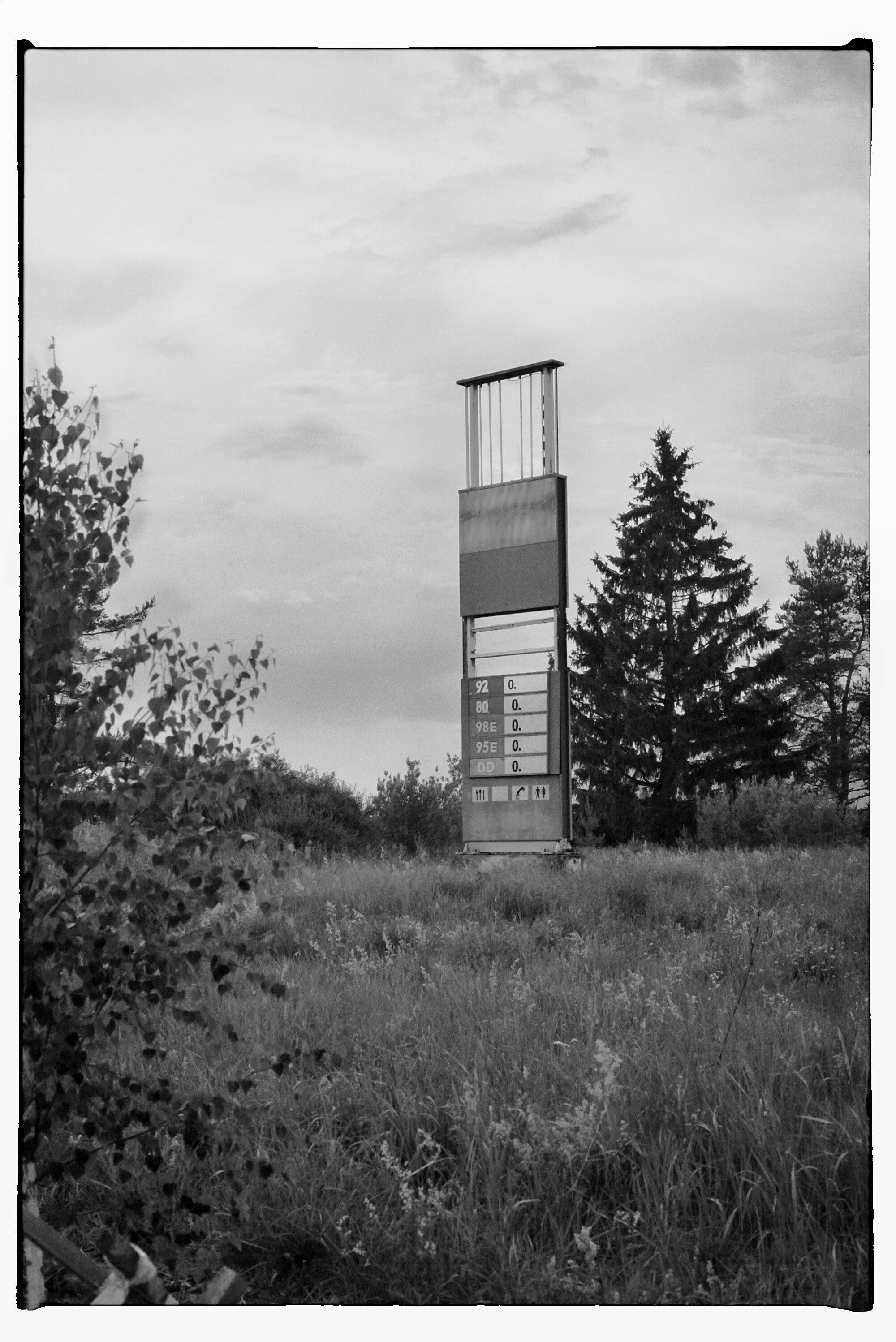

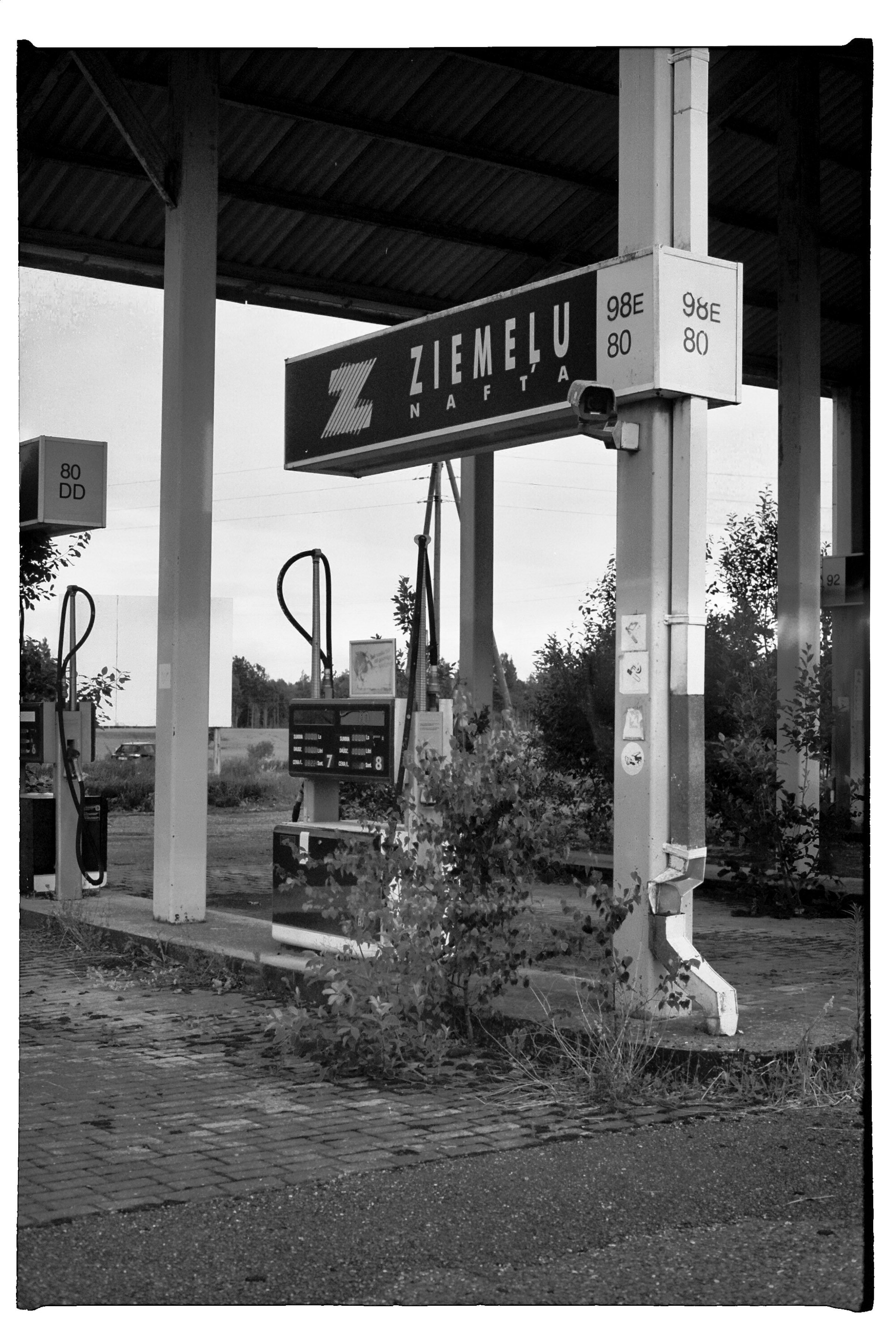

Baltic landscapes

Much of the Baltic landscape consists of rolling hills, with the ocassional small town spinkled in between. The majority of the Baltic population lives in major city centers, and it can be felt the moment one decides to venture into the countryside. Infrastructure in the Baltic states is limited, only one of the three nations has highways. Speed limits of certain roads vary based on the season, with summer allowing speeds up to 120km/h while in winter those speeds might drop down to as low as 100km/h. The countries do however feature a robust and widespread public transportion network. Most small settlements and towns, even individual farmsteads tend to have dedicated bus stops. It seems possible that this is residual infrastructure from the socialist policies of a Soviet past.

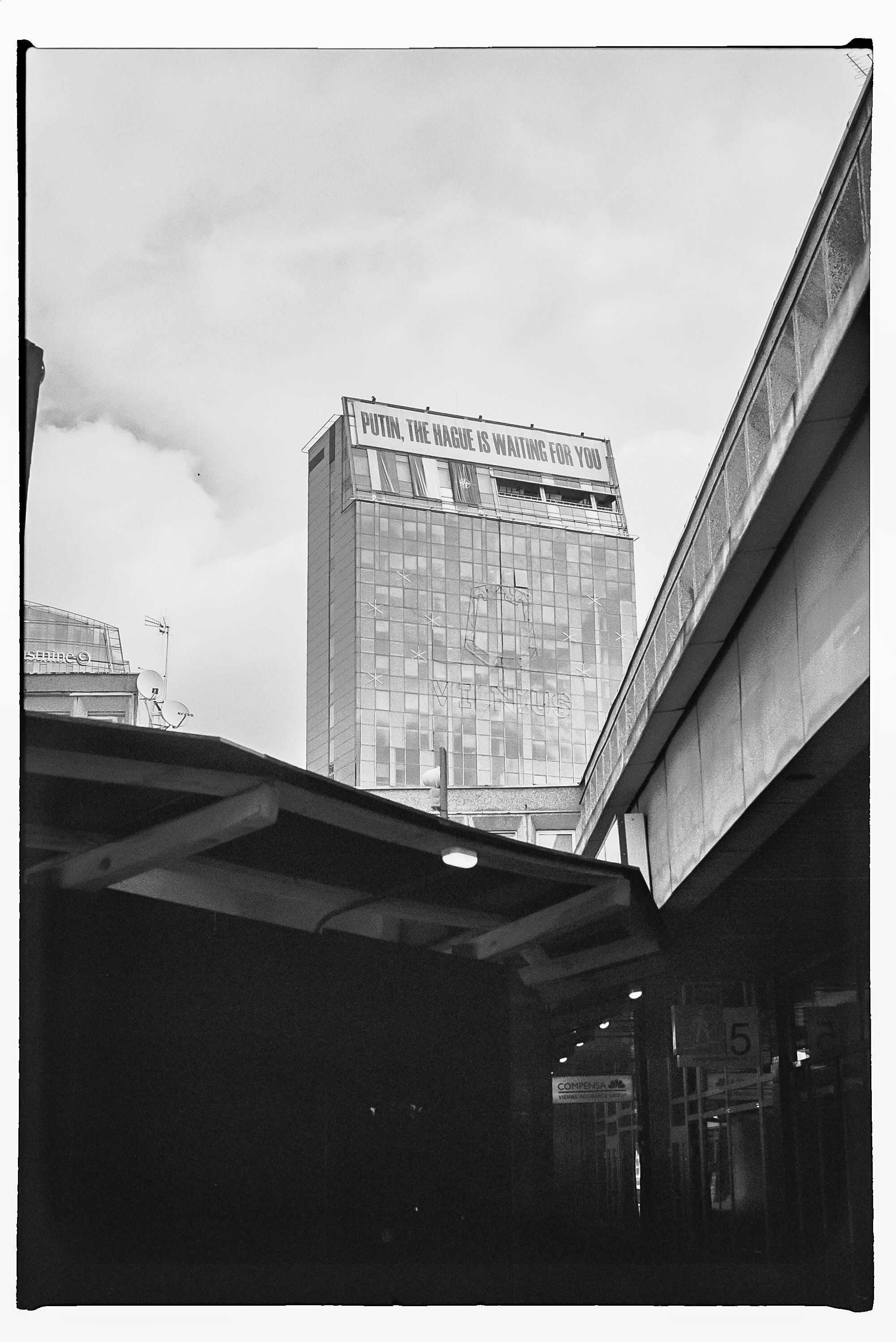

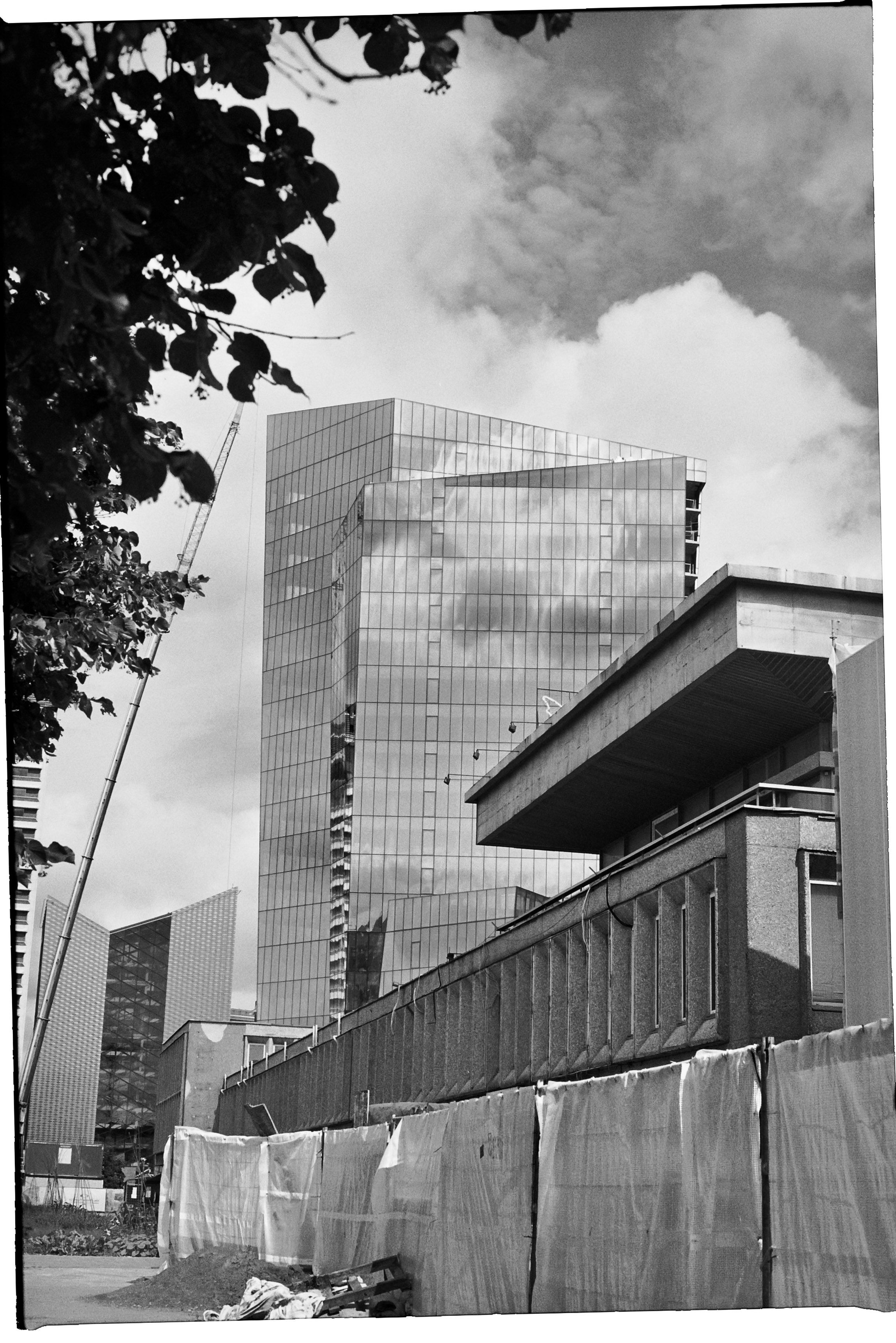

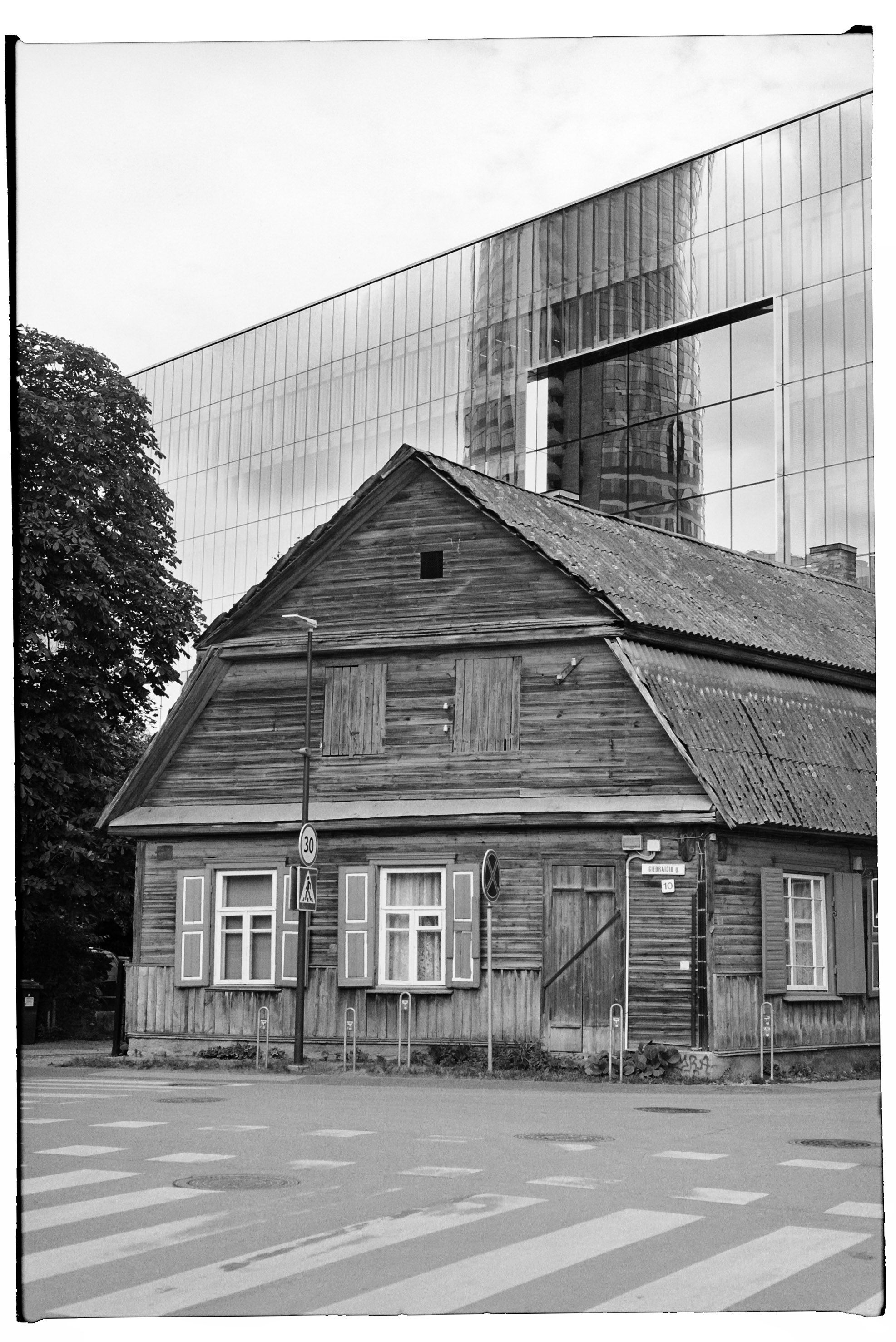

The new Union

When the Soviet Union fell in 1991, all three Baltic states regained their independence as sovereign states. And in 2003, they would be granted membership into the European Union. These nations form the Eastern frontier of the Union, being directly adjacent to what is now the Russian Federation. The war in Ukraine is a big topic in the daily lives of the Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian people. The reason for which can be quite simply deduced from a quick glance at a map. While relatively small, their geopolitical role cannot be overstated. If the Russian Federation decided to invade the Western World, there is a real chance that it would do so through the Baltic nations.